Media: Chapter 1

Chapter 1, “Making Jazz Manouche,” examines the historical development of jazz manouche in relation to ideologies about ethnoracial identity between the mid-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In the decades after Django’s death in 1953, some Manouche communities adopted his music as a familial practice. Simultaneously, critics, promoters, and activists extolled the putative ethnoracial character of this music, giving rise to the “jazz manouche” label as a cornerstone of both socially conscious and profit-generating strategies. Drawing on analyses of published criticism, archival research, and interviews, I argue that these ethnoracial and generic categories have developed together, each informing and reflecting ideologies about ethnoracial identity and its sonic expressions. Jazz manouche grew out of essentializing notions about Manouches, while Manouches have been racialized through reductive narratives about jazz manouche. This chapter traces the historical reception of Django and his cohort to arrive at the living history of jazz manouche in contemporary France and globally.

Image 1.0: “Portrait of Django Reinhardt, Aquarium, New York, N.Y., ca. Nov. 1946.” Photo by William P. Gottlieb. Courtesy of William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress (click here for more information).

Racializing Reinhardt (pp. 33-44)

Audio example 1.1: “Minor Swing” (1937)

Audio example 1.2: “Django’s Tiger” (1946)

Audio example 1.3: “Djangology” (1935)

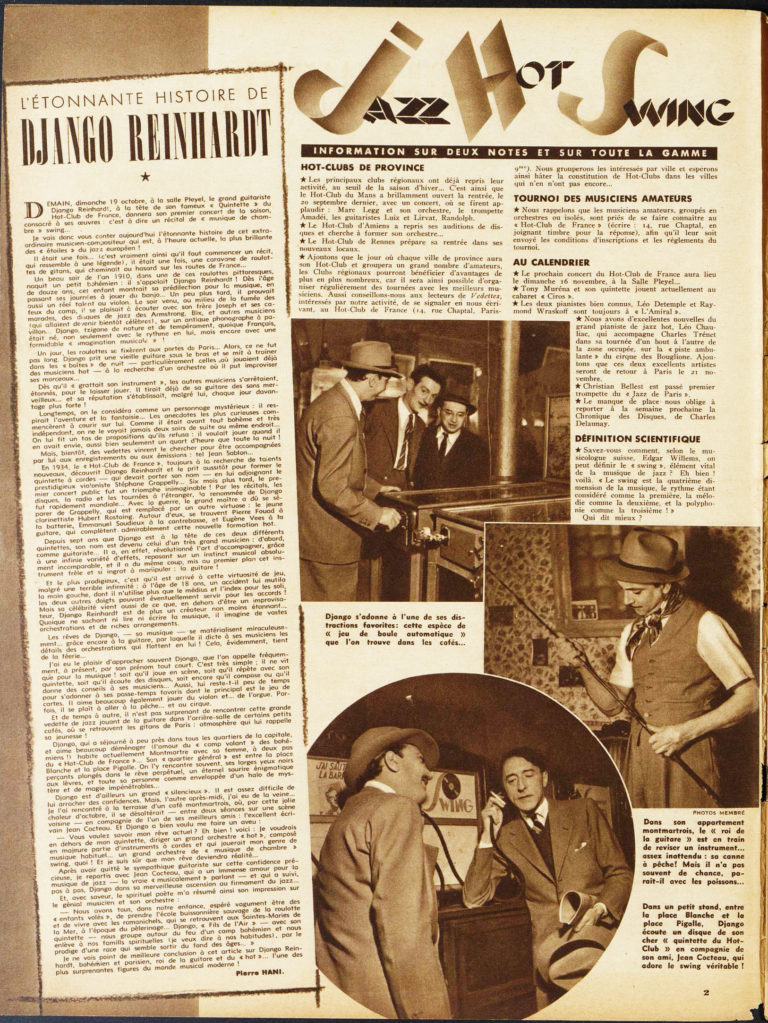

Image 1.1: Feature in Vedettes, 1941

This feature in the variety magazine Vedettes provides a clear example of how Django was racialized during his lifetime. The column on the left side narrates Django’s rise to fame from birth, claiming that “Django, Tzigane by nature and by temperament, although French, was born not only with rhythm inside himself, but even with an astounding ‘musical imagination’!” The author, Pierre Hani, writes that Django “was considered a mysterious figure: he exuded adventure and fantasy,” and that “Since he was above all a Bohemian [a then-common synonym for a Romani person] and very independent, he was never seen two nights in a row in the same place.” He quotes Jean Cocteau making similarly racializing remarks (see Django Generations p. 207, n. 17 for a translation) and remarks of Cocteau’s words, “I don’t see a better conclusion to this article on Django Reinhardt, Bohemian and Parisian, king of the guitar and of ‘hot [jazz]’ … one of the most surprising figures in the modern music world!” To the right of the column are action shots of Django playing pinball, examining his fishing rod, and listening to a Quintette du Hot Club de France album alongside Cocteau. (Image source: cineressources.net)

Videos of Django

Video 1.1: Django Reinhardt and the Quintette du Hot Club de France

Very little footage of Django performing is known to exist. This clip, from a 1939 newsreel titled “Jazz Hot,” shows Django performing a relatively “hot” version of “J’Attendrai” — first solo, then with Stéphane Grappelli, and finally with the whole Quintette. Django’s solo with the group begins at 0:40. Click here for a higher-quality, longer version of this clip.

Video 1.2: Clip from La Route de Bonheur

La Route de Bonheur is better known under its Italian title as Saluti e Baci, a musical film from 1953 featuring a number of popular musicians of the time. This clip shows Django in a train car with, presumably, members of his (fictitious) Romani family offering a newcomer music, food, and libations. The soundtrack is “Nuits de Saint-Germain-des-Prés,” an original Django composition, recorded in March 1952. It reflects the strong influence of bebop in Django’s later style.

Video 1.3: Compilation of Django audio interviews

This video features a series of audio-only interview clips with Django in conjunction with a slideshow and (imperfect) English subtitles.

Jazz, Sinti Political Consciousness, and Musik Deutscher Zigeuner (pp. 46-49)

Styles of Musik Deutscher Zigeuner

Below are three tunes performed by the Schnuckenack Reinhardt Quintett in its distinctive styles influenced by csárdás, jazz, and a fusion of both styles.

Audio example 1.4: “Duj Duj." From the album Musik Deutscher Zigeuner 4, 1972. Variations on this tune are found in Romani repertoires throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

Video example 1.4: "Sweet Georgia Brown." Live performance.

Audio example 1.5: “Lass maro tschatschepen” (pp. 47, 49, 184) alternates between a laid-back, somewhat jazzy verse and a faster, csárdás-like chorus. This song was written by Häns’che Weiss and released on the Häns’che Weiss Quintett album Fünf Jahre Musik Deutscher Zigeuner (1977).

Musik Deutscher Zigeuner in concert

Video 1.5: Häns’che Weiss Quintett performing on a soundstage in 1977.

Video 1.6: Zigeunerfest Darmstadt. This German documentary features Sinti/Manouche musicians from Germany and France. The concert scenes beginning around 11:05 reflect the atmosphere described by Patrick Andresz on p. 50. See part 2 of the documentary here.

Marketing Difference (pp. 59-62)

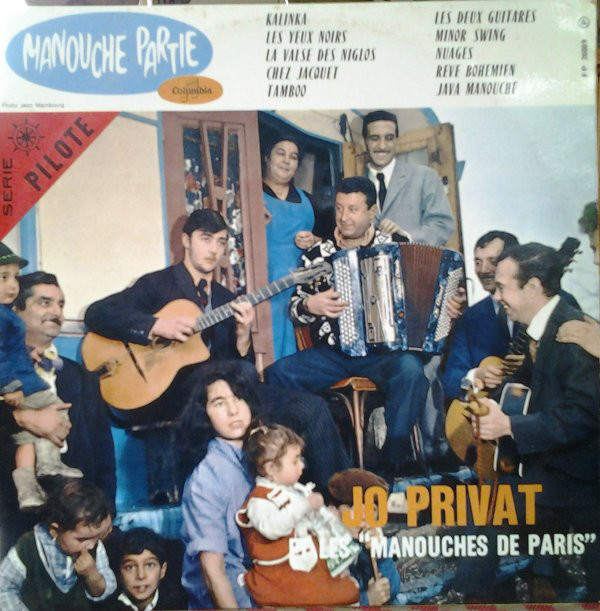

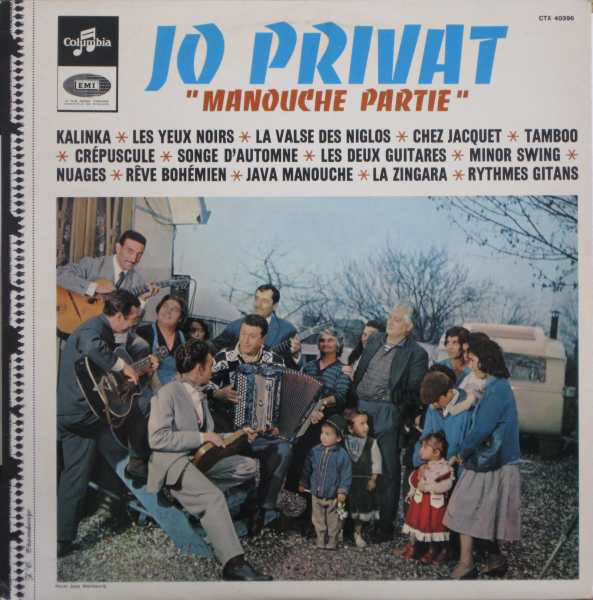

Manouche Partie (LP by Jo Privat)

This album, which has been released several times with slightly different track listings, features Manouche musicians such as Matelo Ferret.

Image 1.2: Manouche Partie album cover (1961 release). Source: Discogs.com.

Image 1.3: Manouche Partie album cover (1966 release). Source: Discogs.com.

Audio example 1.6: Swing 93 by Gypsy Reunion (1994).

Audio example 1.7: Gypsy Music from Alsace by Note Manouche (1994).